Ejsing Church

Ejsing Church is a Romanesque ashlar church with an unusual number of large late Gothic additions. The church represents the story of how local squires influenced the church.

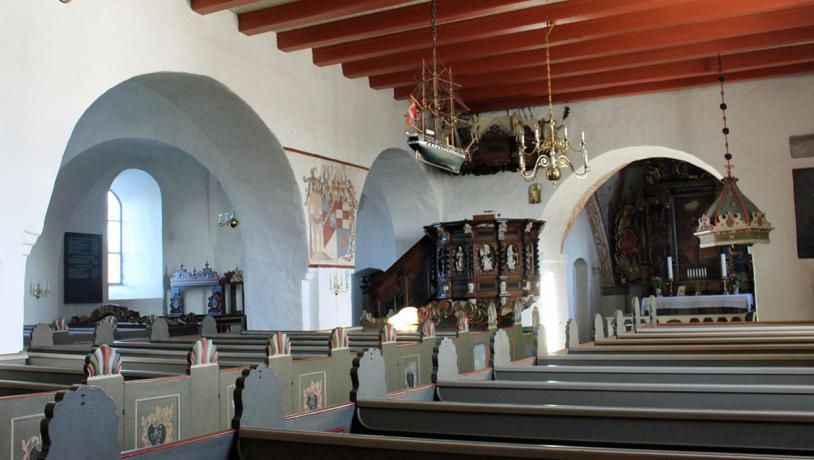

Ejsing Church differs from the other churches in the region by its size, complicated construction and the rich furniture.

Photo:Søren Raarup

A Romanesque Ashlar Church

The church was originally built as an ashlar church with nave and chancel. The relative small ashlars are part of the later additions and alterations of the church which took place in stages during the late Gothic Age. The unusual wealth is linked to the manor “Landting” situatedin a rampart in the large salt marsh area further south. The original Roman nave has a flat ceiling which is common in churches in West Jutland but in the three-winged aisle the ceilings are cross-shaped vaults. The church room sits 330 people but can be extended to sit 500.

Photo:Søren Raarup

Construction Boom and Recession

Ejsing Church is here seen from the north showing the vestry, the three connected side-chapels and the closed chapel. The gables have individual decorations. Building of churches has followed a common pattern across the country, but the size and standards varied. After the prosperity and construction boom of the 1100 and 1200s, the 1300s were a period of recession and crisis. The plague known as “the Black Death” hit Europe hard and decimated the local populations. Many places the parishes were almost deserted. During the 1400s the time of prosperity returned and in the last part of the century and into the 1500s came the next large church-building boom. The style changed from the Romanesque imposing semi-circular arch to the gothics soaring pointed arch. A common feature of Danish village churches was that a tower was added to the west gable and a porch was added to the south entrance, the men’s door. The small Romanesque windows placed up high were widened, at least on the south side and a side chapel was added to several churches. Also the furniture was replaced or complemented, new frescos were added and the old ones painted over.

Photo:Søren Raarup (Kunstværk af H. Bernsdorf)

The Posthumous Reputation of the Wealthy

The extent of the late Gothic additions and alterations turned out very differently in churches in the West of Jutland. The cost of the additions had to be covered by the parish church tithes, but often local squires added additional funds to the projects depending on the size of their manors. There was prestige in showing one’s splendour and wealth and a contribution also served to secure one’s posthumous reputation. This is Ejsing Church an excellent example of. Where poor parishes like Heldum who neither could afford a tower or a porch, or Fousing who had to settle with a modest tower, the owners of the local manor Landting surpassed everyone else even in the time after the late Gothic Age. The Landting history dates back to the 1300s, where there was a large medieval castle (the castle mound still exists) inhabited by wealthy noble families. In the 1600s the medieval castle was replaced with a three-floor Renaissance building. The closing down of the manor around year 1800 also meant that the old buildings were removed.

Photo:Søren Raarup

The Building Today

The original Romanesque church has almost disappeared in the mass of the late Gothic gable and side buildings. The southern chapel is called “the Landting chapel” and was the manor’s chapel, and from the gallery the service could be followed. The furniture shows the influence of the owners from Landting on the church through 2-3 centuries both in size as well as in splendour.

Photo:Søren Raarup

The Ashlar Plinth of the Communion Table

Ejsing Church is distinguished by several late Gothic frescoes from around year 1500. The baptismal font is Romanesque from the church’s construction. It is richly decorated with picture reliefs in a semi-circular arcade as well as the inscription: “In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit”. The original ashlar plinth of the communion table has been preserved, but the stone top was, as in most other churches, discarded after the Reformation. It has been recycled as cut out ashlars under the new late Gothic building, which can be seen on the tower’s south wall, where the middle part of the communion table with the reliquary is inserted. The original ashlars were relatively small with clear traces of wedge-holes made by the mason. To the right the centerpiece of the original stone top from the communion table can be seen. It has a depression which was used to store relics from martyrs.